Similarities Between Lean and Agile

It is said that the difference between theory and practice is greater in practice than in theory. Although I believe this is true of a lot of things, one area that eludes this old saying is the practice of Lean and Agile.

Practicality

The theoretical differences between Lean and Agile are the frequent subject of heated debates, even though their practical implementations often solve many of the same problems. I think those differences aren’t nearly as pronounced as they are often thought to be, and that far too much energy is expended on their account. I suggest we focus instead on getting to the business outcomes we all crave by cherry-picking the best arguments and techniques from each. Let me elaborate:

Origins

Of all the differences I hear about, the most prevalent seems to be that Lean seeks to reduce variability in the work so that the system can be optimized, whereas Agile accepts that variability as inevitable and attempts to adapt for it. This description is not without merit from a historical standpoint. Lean was first popular in traditional large scale manufacturing environments, and Agile sprouted in software development where each unit of work is unique. Though this analysis may be historically accurate, it is also far too shallow for us to conclude that Lean and Agile are fundamentally different.

Practices

The similarities strike me as far more numerous. Both Lean and Agile seek to deliver value to the customer through building the right thing. Both promote a culture of continuous improvement: Lean has kaizen, and Agile has the retrospective. Furthermore, Lean has poka-yoke to mistake-proof problem areas, and Agile similarly promotes the management of technical debt. Both focus on reducing delays. Lean most frequently uses the value stream map as the main tool, while Agile methods often use short iterations for much of the same purpose. Both emphasize the importance of quality. Lean has quality standards, and Agile frequently has a “definition of done.” Both promote resolving blocking issues quickly through all-hands-on-deck approaches. Lean has its andon cord, and Agile often has an impediment identification and removal process. Both promote a reduction of Work In Progress (WIP) for the purpose of accelerating flow. Lean emphasizes single-piece flow; Agile urges people to swarm on a common work increments. The list goes on and on.

Values

The parallels between Lean and Agile are actually not surprising. Indeed, a quick examination of the fundamentals reveals similar values. If one compares the principles that underpin the well-known Agile manifesto with the expression of Lean found in the Shingo Model, one notices a common philosophy.

I think the Shingo Model cornerstones of respect and humility are just a highly condensed expression of the Agile manifesto. What I mean by this is simply that the Agile values (and principles) can be traced back to respect, humility or both. For example, humility is implied in the desire to replace planning with a discovery approach. To arrive at that desire, we must first humbly admit the limits of our knowledge and prediction abilities. Similarly, respect is implied in the belief that people are intrinsically motivated, trustworthy and able of self-organization.

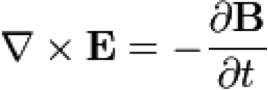

Put another way, Shingo’s respect and humility are to Agile what the Maxwell equation is to the inner workings of electric car propulsion systems. All the information is there, but it has to be unpacked.

Bottom Line

In summary, I believe Lean and Agile are rooted in many of the same principles and values. The challenge of articulating the differences is probably best left to the academics. The doers should focus on taking action instead, because while the differences may be smaller in practice than in theory, practice still makes perfect. I’d love to hear from you if you think this is an oversimplification that obscures some important practical differences.

“Maxwell-Faraday equation”, Maxwell’s equations, Wikimedia, 24 Nov. 2015. Web. 1 Dec. 2015.